2. Clean Slate

HOUGH I WAS ONLY ELEVEN at the time and so many decades have passed, I can still recall in great detail the day we fled Ohio. I remember my Dad, my sister, and me packing the parakeet, the cocker spaniel, and everything else that would fit into our car and the rented trailer behind it. Minutes later, gravel popping from beneath the tires, we crept up behind my stepfather’s house. I still retain what I saw next, that singular, magical vision—my mother, running out the back door, a suitcase flopping in each hand.

In that moment I knew everything was going to be all right.

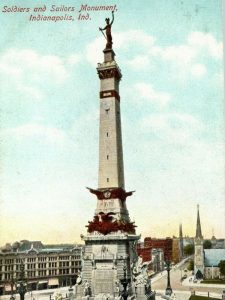

Six hours later I stared in wonder as we circled the towering Soldiers & Sailors roundabout in downtown Indianapolis. That night I thrilled at our first stay in a real motor hotel, followed the next day by another peak experience: my first taste of Dr. Pepper somewhere in Missouri. Soon after, we arrived—safe and sound, we thought—at the little house in Mesquite, Texas, just east of Dallas.

Much of what would happen in the days immediately after was kept secret from this eleven-year-old. But more than a decade later, when in my twenties, my mother told me everything, most importantly why she left us in Dallas and went back to my stepfather in Ohio.

It was that phone call. The threat against her life.

I imagine her stumbling in the dark around unpacked boxes scattered through our little rent house as she tried to find her pastel-blue Princess phone by the light of its rotary dial. In recalling that night all those years later, she told me the voice was not that of her second husband, my stepfather, but of a stranger. “Be on the next plane back or we’ll throw acid in your face and hurt your kids,” it said.

The rest is a mixture of conjecture and imaginings that still blur in my mind, including one false memory of being called out of my sixth-grade class to say goodbye to her. But, years later, in that conversation in her home in Cleveland, she set the record straight about that, too: Within a day or two of receiving the phone call, we’d all gone to Dallas Love Field

together to see her off for her return flight to this man I had grown to hate.

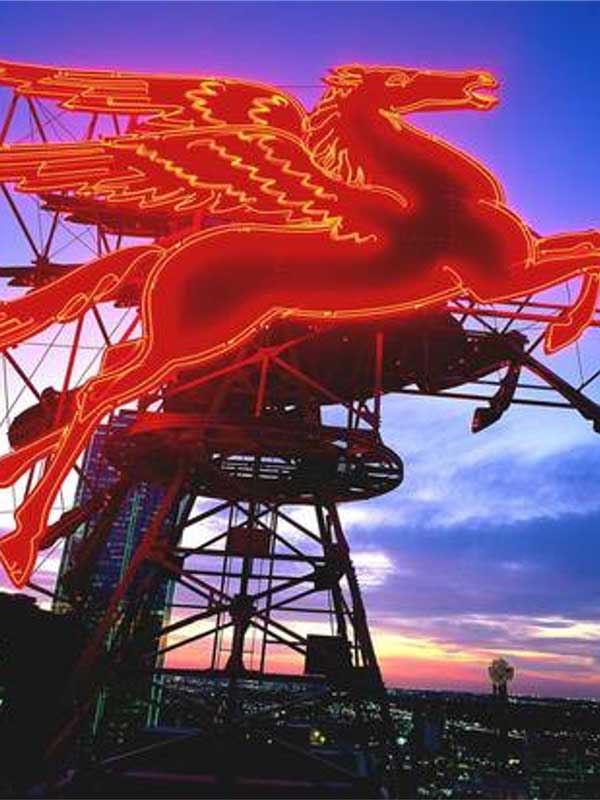

Every year or so I drive by that little house in Mesquite where, as a child, I could go outside at night and just look West to downtown Dallas to see the glowing red Pegasus atop the Mobil Oil building—for me a symbol of my mother’s flight. I can remember a lot from those days, but I have no memory whatsoever of the weeks immediately following her departure. It’s a black hole that now neatly divides my life into two parts: everything before the Princess phone rang that night and everything after.

It would take years for me to see it all more clearly. But when I learned more about my mother’s childhood, I began to understand she had a reason to run. Read about that next.