JAMES MICHAEL STARR

4. Dark History

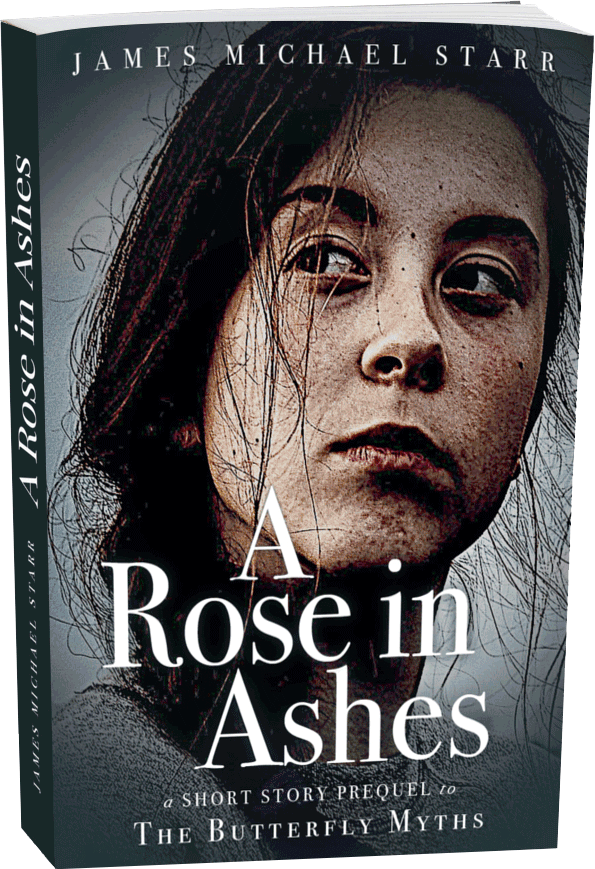

Above: “Children in Midland, Pennsylvania” (1940) by Jack Delano for the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information. Library of Congress

MY MOTHER WAS TEN YEARS OLD in the winter of 1940 when photographer Jack Delano came to town. Employed by the Farm Security Administration component of FDR’s WPA, Delano’s job was to document the living and working conditions of those Americans most sorely affected by the Great Depression.

Midland, at the other end of the state from his home in Philadelphia, offered Delano a convenient set for his tableau vivants of grimy, blue-collar life. It was a company town, its first houses erected earlier that century by the Pittsburg Crucible Steel Company with the goal of providing an ongoing workforce for their profitable new mill. The company house in which my mother lived, at 314 Midland Avenue, stood in the shadow of its smokestacks, possibly among those seen in Delano’s street scene from that winter.

The Library of Congress archives contain more than a hundred photos made in Midland during those years, and in so many of them, Pittsburgh Crucible Steel Company’s hundred-foot stacks loom over every soul, a constant reminder that were it not for steel, this little hairpin turn in the Ohio River might have remained little more than small farms.

Other WPA photographers came there, too, and captured sobering images of tarpaper shacks and slum tenements in which the sole source of running water was an iron pump.

The stark documentary of these mostly black-and-white photos made my mother’s claims of a difficult childhood hard to dismiss. One, shot by Delano around the same time in the nearby town of New Brighton, shows a basement with an open toilet much like the one she described to me.

The protagonist of my first novel, based in part on my mother, is a young singer living in Lindera, Pennsylvania, the fictional counterpart to Midland. Like my mother, Marie Schioppo feels entrapped by the long shadows of the steel mill and is determined to escape.

Marie’s beloved priest confronts her with a metaphysical explanation of the fear that fuels her desire to escape, but she denies it. “I’m not afraid of that place, Father. It’s just a bunch

of grimy buildings.” But he presses her on it. “You want to escape the ugliness. Because you’ve seen the opposite. In fact it was the last thing you saw, in that moment just before you were born. Your soul has made a great passage, a shocking one, so you’ve forgotten.”

She asks what it was she could have seen, and he tells her, “The face of God. In all its beauty. We’re all searching to find our way back. Only the rest of us aren’t as sensitive to it as people like you. Singers, musicians, artists, writers. Poets. You feel it in your bones. When you see beauty you sense you’re drawing near once more. But when you see ugliness, like the tracks, or the mill, the soot and smoke, you know you’re moving farther away, and all you see is shadow. So that’s what you fear. What we all fear. We fear the shadow.”

My mother saw beauty everywhere, but the shadows she encountered kept her on the run. Read about that next.