8. With New Eyes

For the last decade of my mother’s life, and unbeknownst to her, the daughter she’d given up for adoption in 1968 was living just two miles down the road.

N THE 22ND OF JUNE, 2020, I received a somewhat cryptic text message from my last living cousin back east. She was the baby sister to the three boys with whom I’d practically grown up—the three who’d corrupted my childhood innocence with crawl-on-your-belly, sewer-pipe expeditions under the streets of East Liverpool, Ohio, as well as secret missions to lay debris on the railroad tracks just to see it explode.

“I have connected with a new cousin I knew nothing about,” she wrote. “I would like to talk to you about this person if you are open to it.”

I hadn’t seen this cousin since Mom died, and in the decade that followed we had only communicated on a few occasions. Not because I didn’t want to, rather it had simply become my M.O., isolating myself from my past as I’d always done. So given that history, her words seemed a bit odd. Was she so excited about discovering her new relative that she wanted to tell even me, the older cousin in far-away Texas? But something about that phrase, “if you are open to it” suggested there was more to it than that.

So I said, yes, of course I’d like to know, to which she responded, “She would be your half-sister and has been looking for her family for 25 years.”

During the eleven years I was estranged from my mother, and only a couple years after my mob-connected stepfather died, she had become pregnant. In June of 1968, she gave birth to a little girl and put her up for adoption in Cleveland. There she was welcomed into a family and named Jyll.

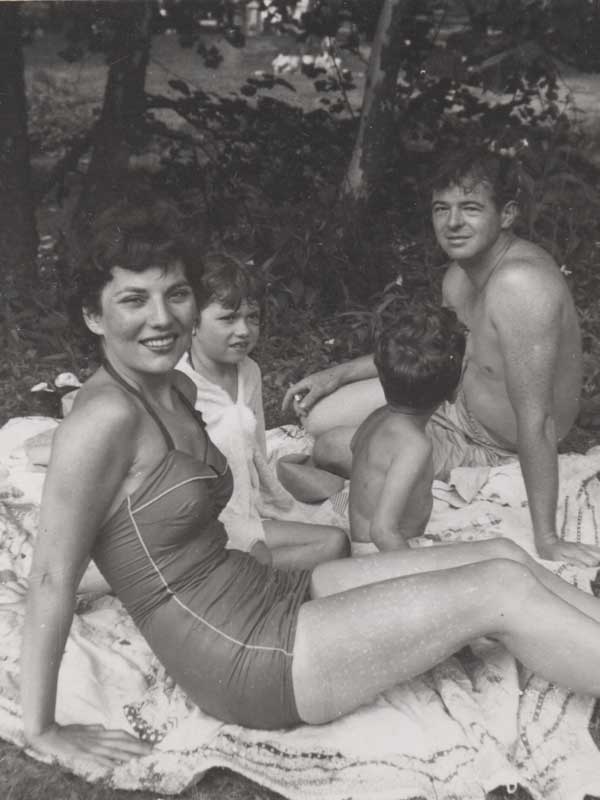

A year after my cousin revealed Jyll’s existence, I was on a plane to Cleveland to celebrate what my new sister described as a very significant birthday. For the first time she wanted to celebrate a date she’d tried to ignore for much of her life. We spent the weekend looking at old family photos to give her a sense of the woman who brought her into this world, and on our last day together, we drove the two hours to East Liverpool so I could show her the setting of our mother’s early years.

I decided on a historical tour, one that would begin at Mom’s childhood home in Midland, then proceed across the Ohio state line to the sad little shotgun house on Daisy Alley where we spent our first few years as a family. From there we drove to every house we lived in up til that fateful day in August of 1962 when we fled Ohio for Texas.

To Jyll, the houses were little more than markers on a timeline. She liked the stories, but what she really wanted to see was the setting for so many of the snapshots I’d shown her from my childhood, Thompson Park. On the drive back to Cleveland she told me why.

She’d actually had a secret agenda in coming to East Liverpool that day—not for my guided tour down memory lane, but instead to seek redemption. And not redemption for herself, but for our mother.

To Jyll, those snapshots of a happy family enjoying a public park suggested Mom’s life wasn’t just pain and loss. True, from a distance, her life appeared to have been a sad one. But the photos in the park were evidence that she had helped raise our family out of near poverty to offer us a measure of happiness. And now that Jyll saw Thompson Park was a real place, she knew she’d found the vindication for our mother that she’d been hoping for.

At the same time I had a revelation of my own.

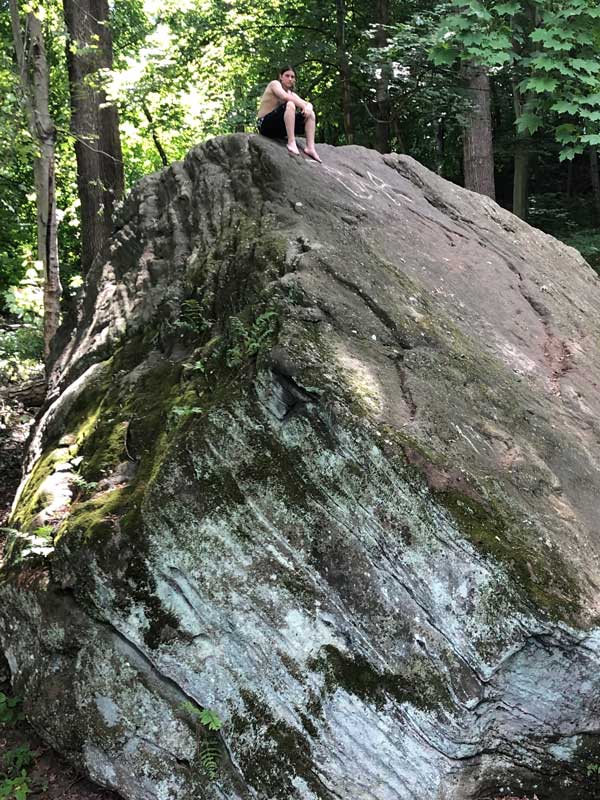

When Jyll and I first arrived at the park I hardly recognized it. But there was one thing that I knew could not have changed: a gigantic rock I played on as a kid.

It was what geologists call an erratic, a massive boulder, as big as a bus, left behind by retreating glaciers 2-million years ago, in the Pleistocene era. We drove around, we parked, we walked.

And we found it. Exactly where I’d left it. It never moved.

And then I had my revelation.

Just like Jyll, I’d found a particular set of old family pictures to be eye opening. But for me they were the ones my mother had taken of a certain deliriously exuberant little boy. In these photos, shot from the time I was a baby and up til that day in Canton when I was eleven, I look like I’m on something. Whether in response to the call, “cheese!”, or caught in a candid moment, I’m loving life and grinning from ear to ear.

But that would change.

I believe that, for many of us, our pre-teenage years are a time when we’re deeply exploring our identity, a time when we’re constantly asking, “Who am I? What am I?” For me, those years began to unfold as I finally started processing my mother’s departure from my life.

One day, in 8th-grade English Literature, I was introduced to Greek Tragedy and the concept of catharsis. I identified strongly with the idea that the loss of my mother could make me stronger. Unfortunately, instead of embracing that wisdom and moving on, I adopted the identity of someone stuck in the tragedy. This was obvious in my art and the writing leading up to my novels.

But finding the massive boulder in Thompson Park again told me that some things never change. I recognized the happy little boy in those family photos, too, and while for years I’d invested in a false identity, I now know he’d been there all along.

And that’s who I really am.