3. Born to Run

“Hell with the lid off” was a term given to steel mills in the old, industrial northeast. Pittsburgh Crucible Steel Company was the one my mother grew up next to.

HEN I WAS THIRTY-SEVEN, my first marriage floundered, then ran aground. And like others who’ve been shipwrecked that way, I found myself confronted by a mutinous band of mental castaways, personal demons who had been, all along and without my knowing it, holed up below decks in my subconscious.

Fortunately, I found a good therapist, one who knew I had to take my share of responsibility for the failure of my marriage. Then, when I just happened to mention, Oh, by the way, my mother left when I was eleven, she also knew to look more closely at the role this may have played in my many fractured relationships with women. She recommended I make, not one, but a series of long-distance phone calls to my estranged mother back in Ohio. My assignment, she said, was to understand what my mother’s own childhood had been like. Not to excuse her for leaving, nor to let her off the hook for any of the choices she’d made, but to benefit from a more balanced understanding of why things had turned out as they had.

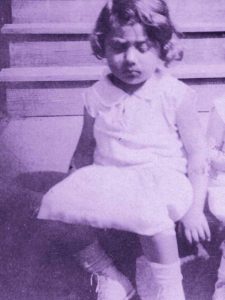

So, with my therapist’s aid and encouragement, I began those conversations with my mother. As it turned out, perhaps because it had been a long time since we had a normal mother-son relationship, she was able to speak freely, as if we were just friends, as if there was no judgment, as if she were merely sharing stories over the back fence with a neighbor. So a little at a time, over the course of several calls, she told the story of her troubled childhood in Midland, Pennsylvania during the waning years of the Great Depression.

I could still hear in her voice the urgency young Joanie must have felt, a desperation to run from the long shadows of the steel mill. And I learned how the stresses of those dark years, combined with my grandfather’s drinking, almost ripped the family apart. No one in our family had ever talked to me about it.

She recalled being dragged by her mother—along with her younger brother and two sisters—from bar to bar, chasing

down my grandfather for money to buy food. And how, when her mother finally had enough and left, they had no place to go but the dirt-floor cellar of a relative. There all five slept in one bed and were forced to use a toilet that sat out in the open.

Slowly the bitterness I’d clung to, believing that at eleven I’d been abandoned by her, began to melt away. I saw the real woman and not the unreachable goddess of my personal mythology. And I could also see how I myself had been born to run, that I too had embraced the irresistible urge to escape the shadow. One might say it had become spliced onto my DNA.

These revelations were just the beginning, and it would still be some time before I could fully understand her. But a door had been opened, and the seeds of my novels, The Butterfly Myths, could take root. Beginning with the research that would fully corroborate the living conditions she’d described. Read about that next.